Load Testing with Gatling 1

It seems to me that performance testing is often neglected and pushed back as a “nice to have” stretch-goal, instead of being a core part of the test automation strategy. So if you’re putting it off because it seems intimidating or difficult, you’ve come to the right place.

A combination of visual explanation, reading, and hands-on tinkering is usually a winner for me, so: I’ve illustrated some concepts (in Part One) talked about design (Part Two), and designed a workshop (in part three). I hope you give it a go!

Part One: Concepts

If you already understand how web apps work and how Gatling actually does load testing, feel free to skip to Part Two to think about designing tests, or to Part Three (coming soon) for some hands-on coding. Otherwise, get ready for analogies, since visualisation, personification, and story-telling are my best friends when it comes to understanding concepts.

Load Testing?

Succinctly from Wikipedia:

Performance testing is in general a testing practice performed to determine how a system performs in terms of responsiveness and stability under a particular workload.

Load testing … is usually conducted to understand the behaviour of the system under a specific expected load. This load can be the expected concurrent number of users on the application performing a specific number of transactions within the set duration. This test will give out the response times of all the important business critical transactions.

There’s plenty of interesting stuff in that article. In fact, the further we read, the more mental tabs might start opening, populated by possibilities intent on waving us over and trying to pull us into strategy meetings. They must wait! Can’t they see we’re still in the Introduction?

Figure 1: A software tester writing their load test and laughing with dramatic glee

Figure 1: A software tester writing their load test and laughing with dramatic glee Why Gatling?

I like using it. Does that qualify as enough justification on it’s own?

Let’s have some reasons, to make it clearer. It’s code oriented, so I can use all the lovely make-life-easier dev practices like source control, peer review, and IDE* integration, aaaand build it into CI/CD* pipelines. Plus, although Gatling is written in Scala, you interact with it using the (easy to understand) DSL*, so no language-specific proficiency is required.

IDE: Integrated Development Environment (e.g. Eclipse, IntelliJ) CI/CD: Continuous Integration / Continuous Deployment DSL: Domain Specific Language

Let’s assume you have buy-in

Let’s skip straight to adoption. Our team see the value in automated performance testing. Whether or not we’re doing CI/CD, we’d all like to know if a build significantly impacts performance, and because we’re advocating for everyone to join in with writing tests (and we want it to be easy to do so) we go with Gatling. A free open-source tool allowing us to write tests as code, in a shared repository, with experimental branches and reviewing possibilities? Yes Please.

Figure 2: A web server receives a tip-off from a worried smartphone regarding some imminent stress testing

Figure 2: A web server receives a tip-off from a worried smartphone regarding some imminent stress testing  Figure 3: The workshy server and their informant flee with packed suitcases

Figure 3: The workshy server and their informant flee with packed suitcases Writing the test is not the hard part

Most guides that I’ve seen jump straight into the how without pausing to consider the why. I’ll admit that it can be fun just playing with shiny gadgets, but when we jump on the trendy trumpet-fan-faring bandwagons of tech without thinking, the outcome is less than ideal.

On a grander scale, I think it’s important to remember that technology is a tool. In today’s (insane, late-stage capitalistic) society it’s easy to demonise tech, since it’s wielded so widely and aggressively in the pursuit of profit, much to our detriment, but ultimately: just a tool.

Figure 4: A smartphone designed to look like a slot machine, operated by a person hungry for their dopamine fix, displays a prompt to refresh for more notification validation

Figure 4: A smartphone designed to look like a slot machine, operated by a person hungry for their dopamine fix, displays a prompt to refresh for more notification validation The thing is, I don’t think that using the tool, or writing the test, is the tricky bit. Knowing what on earth you’re doing in the context of the whole, what to test, what’s representational, meaningful, and useful? That’s the hard part.

Having the knowledge and experience necessary to puzzle out those aspects is what good testers get paid for! That’s not today’s topic, though, so let’s re-focus on the task at hand. Let’s move on to Concepts, since understanding those will help with everything else.

System Under (Intense) Test

With Gatling, our target SUITs are Web Applications.

If it’s running on a web server, accessible over an internet connection, then it’s a Web App, and we can aim Gatling at it to put it under stress. Amazon, Twitter, Spotify, Netflix, Google Docs: all Web Apps.

SUIT: System Under Intense Test

Figure 5: A suited business person with a target pinned to their back receives an increasing number of phone-calls

Figure 5: A suited business person with a target pinned to their back receives an increasing number of phone-calls How do web apps work?

Imagine a Café…

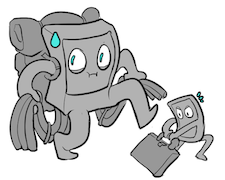

Figure 6: The customer (user) stands to one side of the counter (front-end) in a cafe, ready to place an order from the waiter (server). In the background the menu (API) is shown as a chalkboard with a window looking through into the kitchen (back-end) where the chef (application) is cooking.

Figure 6: The customer (user) stands to one side of the counter (front-end) in a cafe, ready to place an order from the waiter (server). In the background the menu (API) is shown as a chalkboard with a window looking through into the kitchen (back-end) where the chef (application) is cooking. Web Apps have a Front-end (or Client-side) and a Back-end (or Server-side).

The Client-side is, unsurprisingly, where we find the Client. This could be an End-User, using the Twitter app on their smartphone to scroll through their timeline or compose a Tweet (via the UI). It could also be a third-party Consumer such as a WordPress Blog, displaying recent tweets on its homepage (via the API).

UI: User Interface API: Application Programming Interface

On the Server-side we find the application itself. This might be comprised of several components, services, databases, external data providers, and so forth, all the logic and data required to fulfil client requests.

The client-server flow is like placing an order

TODO: Slideshow goes here

Response Time is our Key Metric

When it comes to Web Apps, speed is really important. How long will users wait for a webpage to load? It’s about 3 seconds. There’s plenty of research, and I daresay you may just nod at that stat due to personal experience.

Whether you’re a developer specifically conducting a performance investigation, or a curious tester discovering a performance issue, what you’re seeing on performance test reports are symptoms. In the same way that a high temperature is a symptom of illness in a human, a long response time is a symptom of a deeper issue in an application.

That’s not to say that response time is the only metric, or aspect of the response, that we care about. Just that it’s pretty important.

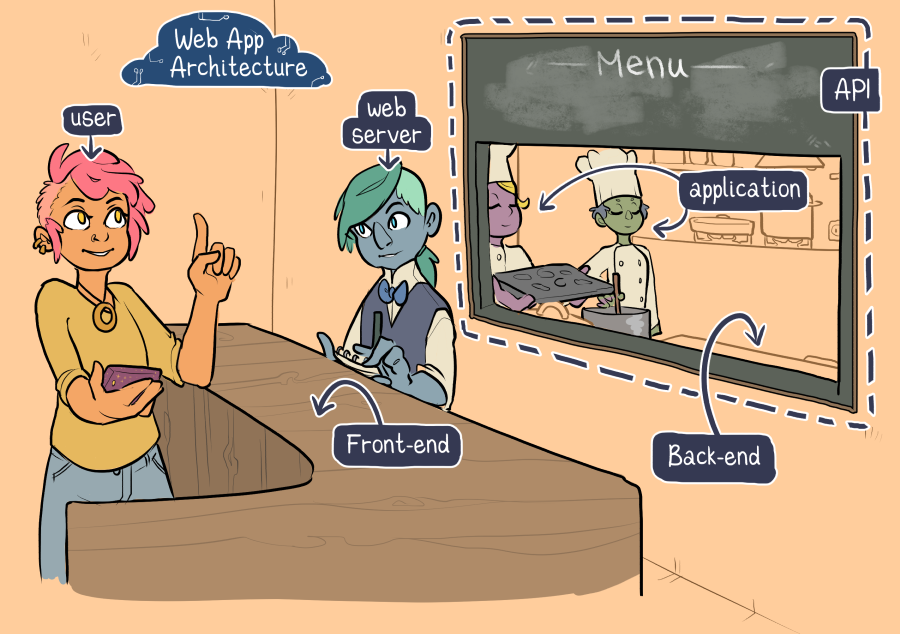

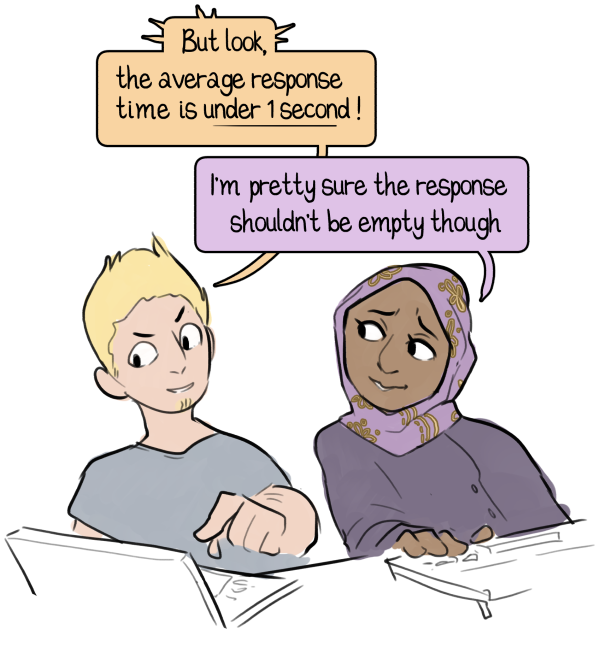

Figure 6: One developer points out to another that a short response time does not mean that everything is fine

Figure 6: One developer points out to another that a short response time does not mean that everything is fine How does Gatling work?

Alright, so interacting with a Web App is a bit like ordering at a food place. How does Gatling go about stressing that system?

TODO: Slideshow goes here

Virtual Users

One of the things I like about Gatling is that it implements virtual users. Not all load testing tools do! Sure, hammering endpoints is fine, maybe that’s all we need if we’re testing a stateless REST API. Not, however, if we know our application is going to have to deal with requests from many concurrent users, each potentially with their own data and behaviours.

REST: REpresentational State Transfer (architectural style for web services)

Scenarios

We can think of our virtual users as actors reading from scripts, that we as directors have given them, in order to represent real users. Those scripts are written in Gatling’s DSL, and might include steps like: go to shop section, wait 2 seconds, select category, wait 3 seconds… and so on.

There are limited paths a user can take through our app, so instead of trying to write 100 unique scripts, we can just pick a few common scenarios, and instead of having one user executing one scenario, we can have a population of X users executing scenario A and a population of Y users executing scenario B (and so on).

Figure 8: The waiter (server) is bombarded with many orders (requests) at once

Figure 8: The waiter (server) is bombarded with many orders (requests) at once Simulations

The simulation is where we describe the user populations, how quickly they’ll be brought into being, which scenarios they’ll be executing (as well as other stuff like config and assertions, which we’ll cover in Part Two).

Let’s say we have a population of 100 users executing scenario A. Do we want all 100 users to start sending their requests to our app at the same time? Ramp up the number of users over a set time? It all depends on what we’re modelling. A learning platform on a Saturday will expect a very different workload than an e-commerce site on Black Friday.

End of Part One

That’s it for concepts! Keep an eye out for Part Two, in which we’ll be examining what good performance looks like, and discussing various aspects of test design (from environment to metrics and working with our team).